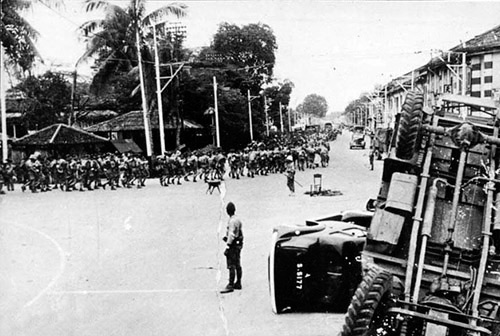

The March to Changi

Having prepared themselves for combat for many months, the thousands of men of the 18th Division never had the opportunity or the resources to prove themselves in action.

Weary from the days and nights of bitter fighting, they had to await their fate, confronted with the harsh reality that they were now prisoners of war at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army.

No longer a fighting force, the men were held at the locations they occupied when the order was given to lay down their arms. Morale was low as they awaited news of their fate. In total, some 90,000 (mainly British and Australian) soldiers had been captured.

Shortly before the formal surrender Allied troops had been given orders to destroy as much ammunition and weapons as possible. They were also busy securing supplies of anything that might be of use to them as captives.

Roy recalled:

After the ceasefire we left the Polo ground and walked down the road to find our vehicles had survived. Not knowing what lay ahead, we filled our packs with as much food and supplies as we could carry.

Two days passed before his unit received orders from their captors that they were to move out and after handing over any remaining weapons they were assembled for the march to Changi.

We were told we would march up to Changi a distance of about 15 miles which took us the best part of a day. Along the way we saw lots of bodies which had been beheaded, we also heard that the Japanese front line troops had been in the Alexandra hospital causing lots of atrocities.

It would be some time later when a full account of the atrocities at the Alexandra hospital (which Roy referred to) would be known. The survivors were so traumatised that they rarely spoke of the events that they had witnessed:

On 14th February 1942 prior to the surrender of Singapore, advancing Japanese troops had approached the Alexandra hospital where a Lieutenant carrying a white flag advanced to meet them. The Japanese killed him.

Japanese troops rushed into the wards and operating theatres and bayoneted over 200 patients and staff members. They removed other patients and staff and locked them up in a staff bungalow nearby. Next day these people were taken out in small groups and either shot, bayoneted or macheted to death. Their bodies were buried in a mass grave.

The death toll from this barbaric act was over 300. There were only five known survivors.

The march to Changi took a full day in the blistering tropical heat. The men laden with their kit-bags and full packs with all their belongings were marched through the streets of the city where they saw the many buildings and homes flattened by the days of constant shelling.

They were also to confronted by the gruesome sight of numerous Chinese who had been killed and beheaded by the advancing Japanese army as well as the many dead Allied soldiers still lying where they had been killed. Even the most hardened of the troops was sickened by what they had witnessed.

To make matters worse crowds of local people jeered and mocked them as they passed.

The Japanese recruited a large number of Indian troops from the captured forces, enticing them to join the pro-Japanese Indian National Army. Many resisted recruitment and became PoW's with the Allied soldiers but a large number of those who deserted were also lining the route, taunting and prodding the soldiers with sticks as they marched past.

They finally arrived at Changi late that day.

Changi was an area to the East of Singapore, the site of a former British Army base. The Japanese decided that this was the place where all the captive troops would be sent. Over the next few days the captured Allied troops from whole of Singapore Island would be given orders to move to Changi.

Many of the British and Dutch soldiers were housed at Roberts Barracks, (a small part of which was used as the hospital), Kitchener Barracks and the surrounding areas. The Australians were housed mainly in the Selerang Barracks and surrounding area.

As the long columns of men arrived at Changi they had to wait in turn to be allocated space in the numerous buildings in the barracks. As far as possible the men were kept with their own units but it was inevitable with the numbers involved that some would become separated.

Changi area of Singapore

The place quickly became overcrowded as more and more men occupied every square foot of the buildings and although the first to arrive were housed on the floors and balconies of the buildings many more were forced to sleep outside in makeshift tents. Conditions were cramped but at least the men were under cover.

At first the officers and NCO’s of their own units remained in charge and food was issued by their own cooks from the tinned food and supplies the men had managed to salvage. The Japanese didn't interfere much with the running of the camp and for a while at least, the men were allowed to move about without restriction albeit within the confines of the barracks area.

For a few days the troops had time to reflect on their situation and what would become of them. It was also a time to reflect on the last days before surrender and of their comrades who were either missing or had been killed by the Japanese.

There was no running water in Changi and for a short time those who were able would walk around a mile to the beaches and bathe in the sea but this practice was soon stopped. Drinking water was also in short supply and had to be brought in from outside the camp. It was then rationed so that every man received only two litres per day.

After a week or so the last of the food supplies retained by the Allied troops ran out and the Japanese started to issue strict rations of rice to the prisoners. The change of diet did not agree with the men with many suffering stomach upsets as a result.

The barracks were holding far in excess of the numbers they were built for and the sanitary conditions were terrible. Latrines were no more than deep pits dug in the ground which inevitably attracted flies and would soon become a source of disease.

The Japanese started to take control of the running of the camp and more guards were moved in. Daily working parties were organised to undertake various tasks. Initially, some groups were taken to the city to help with the cleanup, others were required to remove dead bodies from the area.

Roy was put on a wood chopping party that had to go out into the forests and saw down huge trees for the various camp cookhouses to be used as fuel :

We all kept together in our units or regiments. I was with men from the light mobile detachment RAOC attached to the 18th Division Brigade H.Q. We settled down here for what would be six months or so. We were split up into different sections, me and three or four others were on the wood party. We used to go round the area collecting trees for burning fuel and for cooking.

Sometimes this was a lengthy process, some of the trees were quite large and we used to take them with all the roots and transport them back to camp where we would cut them down to size to use on the wood burning stoves. Other members of our group used to go down to work on the docks.

Time passed and after a month or so illness became more prevalent and lots of our colleagues passed away most of them due to malaria and dysentery. Medical supplies became non existent.

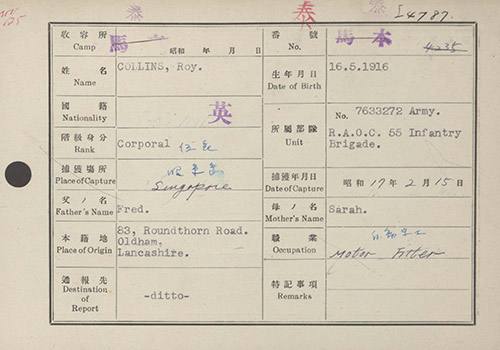

The Japanese compiled a list of all the prisoners and produced index cards to record their details. Around 50,000 of these cards came into the possession of South East Asia Command, who passed them to the War Office in London and they are currently held in the National Archive in Kew. With the exception of his date of birth Roy's details were recorded correctly:

Roy's POW Index Card

Singapore being in the tropics was plagued with mosquitoes and under normal circumstances all the troops would have been billeted in barracks with nets over the beds. No such luxury was available to the prisoners here and at nighttime the air would be full of them. The mosquitoes carried malaria and it would not be long before the makeshift hospital wards were full of men who had succumbed to the disease.

The food rations were now being issued by the Japanese as all other supplies held by the captives had been consumed. Their diet consisted only of servings of white rice and boiled water three times a day, a diet lacking vital vitamins and minerals. Almost half of the captives fell victim to the two conditions that became prevalent among them known as "Happy Feet" and "Changi Balls". Both were diseases arising from Vitamin B12 deficiency. "Happy Feet" meant incessant searing and stabbing pains in the soles of their feet for which there was no relief whereas "Changi Balls" was a vitamin deficiency disease which resulted in swollen itching testicles which became inflamed and raw. After a while other diseases like Dysentery and Beriberi would take their toll.

Posted "Missing"

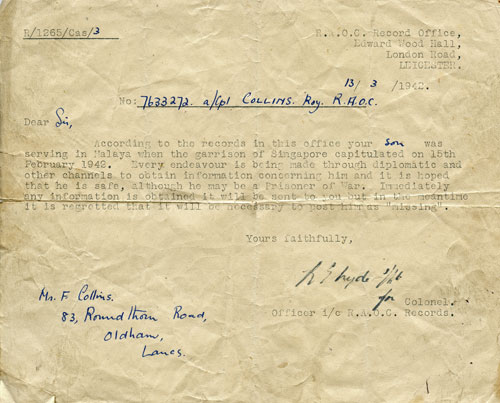

The men had no idea how long their ordeal would last and many wondered if their loved ones back home knew of their whereabouts. Back home it was around a month after the surrender of Singapore when news started to trickle through. In mid March 1942, Roy's father Fred and mother Sarah received the first official news about their son - he was posted as "missing".

Letter posting Roy as "Missing"

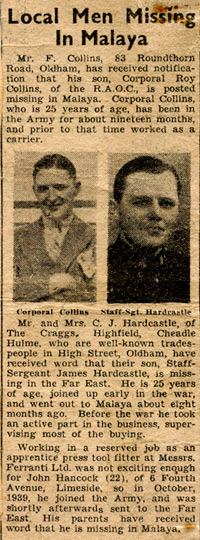

The news about Roy along with that of two other local servicemen was also published in the local newspaper The Oldham Chronicle.

Oldham Evening Chronicle - March 1942

It was not long before the Japanese guards started to impose a more strict regime. Barbed wire fences were erected and the men's free movements within the camp became more restricted. Unless they were sick all the men were expected to work either for the Japanese or in providing wood and water for their units. They were also told that they must salute or bow to all Japanese soldiers. A refusal to comply would result in either a slapped face or in some cases a severe beating. This violence would only increase as the days went by.

In their spare time the men organised whatever form of entertainment they were able, cricket matches and theatrical productions all helped to lift their spirits and stave off the boredom.

As the weeks passed more men became sick. Malaria and Beriberi were now rife and although the Japanese had adequate medical supplies and equipment to treat these debilitating diseases they failed to pass any on to the troops. Orders were given that all water supplies had to be boiled to minimise the spread of disease.

It was in August 1942 when Roy had his first stay in the camp hospital after an attack of Dysentery which was now becoming prevalent amongst the troops. Without treatment men could lose weight very quickly. Fortunately Roy had contracted the milder 'bacillary' form and quickly recovered. The more serious 'cerebral' form often proved fatal.

The doctors had to carry out procedures and operations in makeshift theatres using implements that had been improvised and all the while a steady stream of the dead were being taken through the gates for burial. The Scots regiments would honour their fallen comrades with a piper playing a lament ahead of the procession and the sound would be heard all around the camp.

My dad was a keen musician and enjoyed many genres and styles of music. In later years after the war he would always express a displeasure when the bagpipes were played and I could never understand the reason for this. I think I now know the reason why.

The Selerang Incident

In August that year five prisoners were caught trying to escape. This prompted the Japanese commanders to issue a form to all the men to ordering them to sign a promise not to attempt to escape. The officers told the men that they must not sign and thus a majority of them refused. The following day they were told that if they continued their defiance they would be moved to Selerang Barracks a few miles away. They again refused to sign and the order was given for them to be moved that same day.

Roy recalled the incident:

There was an incident took place around August when everyone received a letter asking them to sign saying that they would not try to escape. We were told to ignore this request. Consequently we were told the whole of Changi would be moved to a barracks called Selerang which used to house 800 men.

The whole of Changi consisted of around 15,000 including the hospital and we all made our own way to Selerang which was about five miles away. Finally the whole of Changi was congregated within the confines of the barracks. We seemed to be sleeping shoulder to shoulder. We were put on food and water rations consisting of around half a pint of water and a meal of rice and stew, daily. After a day or two passed, conditions began to deteriorate and Dysentery, malaria etc became prevalent.

We received news that PoW’s had been captured up in Malaya and taken to Changi. It was reported that they were shot on the beaches. The allied forces who witnessed the shooting were overwhelmed by the way it was carried out.

Obviously our current situation could not last and on the fifth day we were told we would all return to Changi. We were told we could sign the escape forms but disregard the consequences. Everyone returned to their own billets and things carried on as before.

All officers over the rank of L/Colonel received word that they would be transported to Japan along with some ordinary ranks but in the end only the higher ranks sailed.

Selerang Barracks was designed to accommodate a regiment of 1,000 men.

The barrack area was only a few hundred yards square and the men in their makeshift tents occupied every square inch of it.

Up to 15,000 men occupied every available space on all three floors, verandas and roofs of the barrack buildings. Conditions would rapidly deteriorate and Dysentery soon began to spread throughout the camp. The men were told they would remain here until the 'no escape' forms had all been signed.

Only one water tap was made available and the men had to queue for hours to obtain their daily ration of around two pints.

On the third day the men were still defiant so the Japanese threatened to bring in around 2,000 hospital patients who had been excluded in the move from Changi.

The following day, the Japanese took the five prisoners who had attempted to escape down to Changi beach and executed them in front of their officers. The barbaric scene was witnesses by Arthur Lane who served in Malaya and was later the founder of The National Ex-Services Association :

Of lasting memory are the two executions I witnessed. The first officially I attended as a bugler. The padre and I were to attend for the purpose of creating a military style performance. Also to attend was Colonel C Wild to act as interpreter.

The following day the 2nd September I will always remember for its typical Japanese barbarism. When we arrived at the scene a large group of Japanese soldiers and civilians were already waiting for the carnival to commence. A truck arrived from Changi prison. The back was dropped down and the prisoners ordered to get down. One of the prisoners was wearing his pyjamas having been brought from the hospital. He could not walk or even stand on his own, so he was assisted by the Padre and one of the other officers.

The prisoner’s names and army details were read out parrot fashion. 7591250 Private Fletcher (RAOC), 6140961 Private Waters (East Surrey), 1573184 Private Nurse (Royal Artillery), VX63100 Private Breavington (AIF), VX 62289 Private Gale (AIF). Private Waters had been injured during the fighting and was suffering with Pneumonia due to lack of attention. The four able men were taken to a position where five pieces of wood were protruding from the ground. Each one was placed in position in front of each pole and secured by rope. The fourth man was carried to sit upright. There was a preamble in Japanese read out loud, which I believe was the sentence of death issued by the Japanese court, this followed with two Japanese officers performing some form of salute using the swords. There was a deal of muttering coming from the English speaking witnesses, with colonel Wild stating that the men had not received a fair trial. While this was going on ten Japanese soldiers were marched in line facing the prisoners. A Japanese officer shouted orders which were repeated by the Japanese gunso (sergeant) at which the ten men raggedly lifted their rifles to the aiming position. The order to fire was again given by the officer which in turn was repeated by the gunso. The double order caused confusion among the soldiers as each one fired indiscriminately. The officer shouted out some kind of instruction and one or two of the executioners started to shoot at Pte. Waters who was sitting on the ground. Further confusion followed as one or two of the men fell forward their bonds broke loose. The Japanese soldiers must have imagined that the prisoners were about to escape and they immediately started to fire indiscriminately. Above the shots could be heard our own officers shouting and swearing and the Japanese officer trying to regain control.

Moving 'Up Country'

It was now early September and for some time there had been rumours amongst the prisoners in Changi that they were going to be relocated to other areas 'up country'. Some units had already left a few weeks earlier but no one knew where they had been moved to. The Japanese guards told some of the men that they would be going to rest camps where they would only be expected to perform light duties. Others were told that camps were being prepared by the Red Cross to provide rest and medical care for the sick.

The number of prisoners at Changi had already reduced as men were moved out to work for the Japanese in Singapore but week by week a steady stream of units began to leave for unknown destinations 'up country'.

The men were organised in groups under their own command which were then subdivided into 'Letter Parties'.

The first Mainland Party (known as the No.1 Group) of 3000 British had already left Singapore on June 18, 20, 22, 24/26th 1942, their task initially was to build the camp at Nong Pladuc to house future work parties en route for up country.

A further four groups (2,3,4 and 5) made up of 3200, 791, 2600 and 1300 troops left Singapore between 9th and 24th October 1942.

The largest movement of mainly British prisoners known as No 6 Group was made up of letter parties:

Letter Parties X, W, V, U, T, S, R. Lt Col C.E Morrison senior officer with six other Lt Colonels in charge of each Letter Party. A total of 4550 British (seven lots of 650) departed Singapore on the 25th, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31st October 1942.

Letter Parties Q, P, O, N, M, L. Lt Col D.R Thomas senior Officer with six other Lt Colonels travelling with each party. A total number of 3900, departed Singapore 1st, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6th November 1942. The combined Letter parties made up six separate train lots of 650.

Many thousands more British, Dutch and Australian troops would follow them over the next ten months.

The day finally arrived when Roy's unit were given the order to leave Changi. He recorded the date of his departure as 27th October 1942 but it was not until the 31st October when he would travel with a unit of 650 men in the 'R' party under commanding officer Lt. Col. Heath. The only thing they knew was that they would be travelling from Singapore by train and were told to take with them everything they could carry as they would not be returning.