Leaving Nong Pladuk for Ubon

By the early part of 1945 the Japanese were beginning to suffer heavy losses in Burma. The railway had been repeatedly damaged through the constant Allied bombing raids and became of limited use to their war effort. They started to concentrate their efforts in others areas and as a result many of the prisoners in the railway camps were relocated.

Large groups of prisoners began departing from Nong Pladuk and around the mid February it was Roy's turn to leave. The men had no idea where they would end up as they were marched to the railway station and once again herded into cattle trucks. Their journey would last for several days with the first stop at Bangkok and from there travelling a distance of around 380 miles to Ubon in the North East of Thailand.

We were travelling for four or five days in the cattle trucks passing through Bangkok until we reached our destination, a place called Ubon or Ubol which was situated on a river bank. We travelled from the railway terminus to the rivers edge… When, eventually the boats were unloaded we prepared for an 18 mile journey to the camp we would be occupying for the next few months.

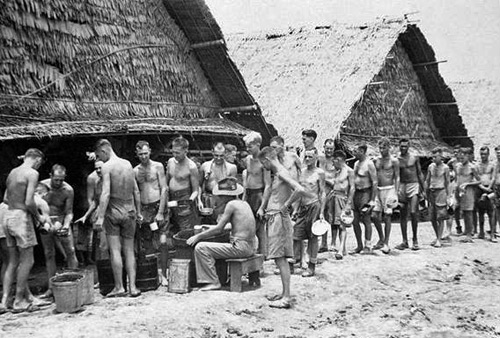

When we arrived there we were absolutely exhausted. The place where we were dropped off was just an empty area of ground with no sign of any buildings. To our amazement those in our group who had any experience of building with bamboo were seconded to building parties. This eliminated the likes of me.

Map of Thailand showing the proximity of Ubon to Bangkok - a distance of approx. 380 miles

The men in Roy's group were among the first to arrive at Ubon Camp. Their first job was to build accommodation and kitchen buildings but the Japanese had other ideas and after the second day the men were set to work. They would be expected to complete the building of their accommodation at the end of each days work and in the meantime they had to sleep in the open.

On the first day the building parties were put to work with bamboo and attap (made from palm leaves), this was used to form a roof. When this was erected we each claimed a piece of land to sleep on. We used a rice sack as a blanket.

On the following day there was a hive of activity around the camp. The builders were in action again this time erecting a cookhouse. This consisted of what they called qualys?? They looked like giant steel huts and in this they placed an oven made of clay bricks with a hearth underneath. It didn't take long to make a meal after they were done with this.

The day after we were divided into working parties, I was in charge of a platoon of thirty men. We were allotted to go down to build airstrips on the borders of Ubon.

Ubon camp was in a remote area of Thailand near the town of Ubon Ratchathani and was was chosen by the Japanese to house prisoners who would work on the construction of nearby airfields for the Japanese Airforce.

Life was just as hard for the prisoners and more months of enforced labour lay ahead, clearing the jungle, quarrying and moving large amounts of earth and stone to lay the foundations for the airstrips. Roy recalled the daily work routine:

Every day about 200 of us lined up outside the cookhouse for rations for lunch. The rations were rice and potato shoots. One morning the lad on the shoots was too generous with the portions and this meant that several chaps were without the main part of the meal.

I went to the cookhouse for extra rations but they had nothing left. I refused to go to work until we received something and eventually the Japs came to see what was going on. After heated exchanges between the three parties, the head of the cookhouse agreed to give us Demerara sugar.

We started off to work, a gap at the front of the column and a gap at the rear along a straight dirt road about 9 ft wide all the way to Ubon. We eventually arrived around midday having travelled a distance of around 15 kilometers to the airstrip; it was a long hard walk with only two stops on the way.

The guard met us there and we were split into two groups building runways in the trees for camouflage. We had our lunch of rice and Demerara sugar. As for drinks we had what they called tea boys who collected water from the nearest well and boiled it in forty gallon drums.

We carried on working in the afternoon, clearing the trees until 6.00 pm when we started to make our way back to camp. It was comical that the ones with the shoes on set the pace which made it almost impossible to keep up. After much shouting to the leaders we managed to compromise on a more acceptable pace.

This daily journey continued for many months . . . . .

The camp at Ubon eventually housed around 3500 prisoners who felt increasingly more isolated from the outside world. One reason for this was that radios which had been concealed in some of the main railway camps did not exist at Ubon. News of the war effort in Europe and the progress of the Allied forces in the Pacific was now the subject of rumours.

Roy recalled that on many of their daily journeys to and from the airstrip they would hear calls from the Thais informing the working parties about the war effort against the Japanese. Unfortunately the language barrier meant that some of this information could not be accurately interpreted or relied on.

By early May work on the airfield was considered to be going so well that the camp commander Major Chida allowed the troops to to start organising their own entertainment and producing shows for the camp. This small concession did help to lift their spirits and was a great boost to their morale.

In July although most airstrips were nearing completion, orders were received to stop work. Much to the amazement of the men they were told to start digging deep trenches across the runways they had just made. Rumours and speculation were rife as to why this was being done. The prisoners began to think that either the war was over or perhaps that the Japanese were nearing defeat but whatever was happening life in the camp continued as normal.

What the prisoners didn't know was that the Japanese were preparing for the possibility of defeat by the Allies and had drawn up plans for such an eventuality which included the execution of PoW's. After the war papers were discovered which were issued to camp commanders. One of them read:

" Extreme measures to be taken against PoWs' urgent situation. Whether they are destroyed individually or in groups, or however it is done, with mass bombing, poisonous smoke, poisons, drowning, decapitation, or what, dispose of the prisoners as the situation dictates. In any case it is the aim not to allow the escape of a single one, to annihilate them all, and not to leave any traces. "

Rumours about the Allied forces successes became more persistent and by early August the men sensed that something was about to happen. Another indication was that the guards became less hostile to the prisoners and it was around the second week in August that the camp was given a 'rest day' so that the Japanese could celebrate the Emperors birthday. However, the following day there were no working parties either, leaving the men to speculate on what might be happening. Their hopes were shattered the next day when working parties resumed but the Japanese and Korean guards appeared to be very agitated.

The War is Over

On the evening of the 18th August the camp was assembled for the usual roll call but they were told that an announcement was going to be made by the Camp Commander Major Chida. The Major stood on a platform and through an interpreter announced that “The Greater East-Asia War is over”. He went on to say that the prisoners were now free men.

Roy recalled that the announcement was greeted initially with a stunned silence but after a short while after the news began to sink in there was cheering and singing with a sense of total elation. Men were moved to tears as they tried to comprehend what many thought would never happen.

Although the men didn't know about it at that time, a few days before the US had dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and it was this act that brought about the Japanese surrender.

After the initial euphoria and celebrations had died down the men began looking forward to their freedom. There was still confusion amongst their captors and the Allies and although they no longer had to form the daily work parties camp life would continue for a while longer.

Because the prisoners were in an isolated area, some of the first essential supplies to the camp had to be dropped by parachute from Allied planes. Conditions began to improve day by day and the long awaited medical supplies and Red Cross clothing confiscated by the Japanese were finally made available. Food rations also became more plentiful and the daily diet of rice and stew had come to an end. Another boost to morale was provided by the resident players and musicians who put on daily entertainment in their improvised theatre.

The men soon became restless and anxious to leave the camp but it would be several more weeks before they could start their journey home.