Ban Pong - Thailand

On 31st October 1942 after being held captive at Changi for just over 8 months, Roy and the 650 men in the 'R' party were ordered to gather whatever they could carry for a march to the railway station at Singapore. What the men didn't know was that they would be used as forced labour to build the 288 mile railway from Thanbyuzayat to Ban Pong. This would join up with the Bangkok to Singapore line and would be of huge strategic importance to the Japanese.

They were herded into steel cattle trucks, around thirty men to each one. With little enough room to stand or sit up it was impossible for them all to lie down in this cramped space. In the searing heat the trucks were like ovens during the day but became ice boxes during the night. To make matters worse many of the men were suffering with dysentery and as there were no toilet facilities the men had to resort to hanging out of the moving train while their comrades held on tightly to their hands.

Roy recalled the journey:

Towards May rumours circulated round saying many of us would be transported to new camps up in Thailand. This in fact materialised when in October, several hundred us were taken by cattle truck to [Bangkok] Ban Pong.

We travelled for about five or six days stopping only in lay-by’s to satisfy the call of nature. Those who didn't’t make the stops had to hang out of the moving carriages held only by a rope.. During the journey we were fed a diet of boiled rice which was prepared using boiling water from the engine. We finally reached our destination on the fifth day of our journey.

The train travelled over a thousand miles from Singapore to Ban Pong in Thailand making only three short stops a day when the men were allows to stretch their legs, attend to the call of nature and feed on a meal of rice and water. Some of the men had managed to get hold of Red Cross food parcels before leaving Singapore and these were shared amongst them. These would probably be the last Red Cross supplies they would see for some time to come as the Japanese would confiscate any future supplies for their own use.

When they arrived after travelling for six days in inhumane conditions the men were demoralised, hungry and exhausted. After disembarking the train at Ban Pong station they were assembled and counted after which they were told by a Japanese officer what lay ahead for them.

They learned that they were going to build a railway linking Bangkok with Burma. The railway would run from Nong Pladuk through over 280 miles of jungle to Thanbyuzayat in Burma. A proposal for this construction had been rejected before the war by British engineers who said it was near impossible to complete without a large workforce and would incur a high number of casualties. The railway when completed would be of huge strategic importance to the Japanese and allow their advance towards India.

The railway would follow the course of the Khwae Noi River northwards for most of the route. This would be a great advantage for the movement of men and materials as the building work progressed. Most of the line passed through dense jungle and it would be the task of the prisoners to build the hundred or so work and transit camps located at various points along the intended route of the railway. Work was to start at both ends of the railway so for the troops this could mean either a relatively short journey or it could involve an arduous trek lasting for many days and stopping at the many transit camps along the way. The Japanese plan was to complete the railway by December 1943.

The area around Ban Pong station would be the first Transit camp for men arriving from Singapore. It was divided into two sections of bamboo huts, one for transit and one permanent. The site was filthy and infested with mosquitos with stagnant pools all around. It was often flooded especially during the wet months of the monsoon season. In the coming months many thousands of prisoners would arrive at this camp before being dispersed to their next destination.

Map showing the route of the Thailand-Burma Railway

After the first taste of their temporary residence the troops soon realised that the Japanese promises of rest camps and better conditions were a lie.

The 'Death Railway'

It is from this point in time until around twelve months later that Roy's precise movements become unclear. During his time as a prisoner, he (like many of his comrades) stayed at several camps along the railway. To try and follow his movements I have used information gathered from many sources including his own written and oral recollections.

One of the sources is his Liberation Questionnaire. At the end of the war before the troops were repatriated many of them were interviewed by MI9 and asked to complete the form with details of their movements, camps where they were imprisoned and the dates they were there. They were also asked about escape attempts and sabotage. According to the information on Roy's liberation questionnaire, his next camp after Changi was Nong Pladuk where he was under the command of Colonel Toosey.

It is well documented that Lt. Colonel Toosey was the CO at Nong Pladuk but he didn't arrive there until December 1943. Prior to that he had been the senior officer in charge of the bridge building camp at Tamarkan.

However, in one of Roy's notes he wrote:

From Banpong we were transported to a camp called Kanchan. From there we were transferred into river barges which took us across the river. As we sailed across the river some of the barges were taking on water and we had to bale water out with petrol cans.

From the layout of the camps (and on the assumption that Kanchan was Kanchanaburi) a river crossing from there would have taken him to Chungkai camp. From other information I have received I know that one of his comrades from the RAOC, George Cross (who became a lifelong friend of Roy's after the war) left Singapore with him in the 'R' party. George's first camp after Changi was recorded as Chungkai, so unless they became separated at some point in their journey it is possible that Roy was at Chungkai for several months before his move to Nong Pladuk.

The camp at Kanchanaburi was a march of around 40 miles from Ban Pong and to reach Chungkai they would have crossed the Mae Klong [later known as the Kwai river] in big wooden boats operated by Thai natives.

From the opposite side of the river bank Chungkai camp was only a few miles away.

Chungkai (also known as Kao Poon) was one of the larger work camps situated on the bank of the Mae Klong river. It was a distance of 60km from Nong Pladuk in the south and 355 km from Thanbyuzayat in the north and it also acted as a transit camp for the many men working on other parts of the line. Throughout the course of the railway construction it would be expanded to accommodate one of the main hospital camps for PoW's on the railway. Today it is the site of a war cemetery.

Between Kanchanaburi and to the north of Chungkai was the Tamarkan camp. The men at this camp were under the command of Colonel Toosey and were responsible for building the wooden and steel bridges across the Kwai Noi, which would become the subject of the woefuly inaccurate film Bridge over the River Kwai made in 1961.

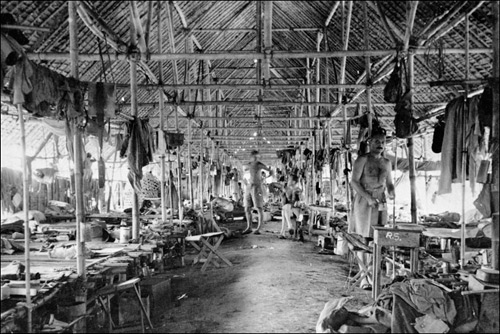

The Chungkai, Kanchanaburi and Tamarkan camps in common with most others along the railway consisted of long huts (often up to 100yds long) built from bamboo poles with a raised floor and covered with an attap roof. Attap was a traditional material in the far east of Asia, named after the attap palm which provided the leaves with which the roofs of the huts were thatched.

The long and narrow huts were filled with rows of raised bed platforms along each side with a narrow passageway running down the middle. This communal space was limited such that each man was allotted a width of about two feet of sleeping and living space.

The first working party to arrive at any of the areas designated as camp sites had the job of clearing the area of trees and vegetation to allow construction of the camp buildings. This was often a hazardous process since most of the jungle was home to a variety of venomous snakes, scorpions and lizards. Long lengths of bamboo were then collected and bound together to make a framework onto which the thatch palm would be laid. Slats of split bamboo served as beds. While this building work was undertaken the troops had to sleep under canvas or at times in the open.

The prisoners were only allowed a short time to settle in to camp before they were put to work building the railway. Organised in working gangs under the supervision of Japanese Engineer Officers they were set the task of clearing areas of jungle, earth moving, laying embankments, building bridges and whatever else was required to make a path for the railway. Once the engineers had given instructions for the days work, Japanese guards would make sure that it was carried out.

A typical day went as follows:

Up at daybreak, had rice breakfast, walked the about a half a mile and paraded outside the Japanese tool shed. Collected tools of metre measuring sticks, changkuls, picks, spades, baskets and stretchers (for carrying the earth). Then walked to the railway trace, where a thirty yard across stretch of jungle had been cleared by earlier prisoners.

The embankment ran along the centre of this clearing and the Japanese had put a bamboo stake structure to get the proposed embankment height right, this varied between four to twenty feet. The days work load was to build the embankment, this was made by splitting the men into three groups. One third of the prisoners dug out the earth each side of the railway trace and put the earth in the baskets or on the stretchers.

The next group carried the earth to the embankment where the earth was off-loaded. The final group spread and trimmed the earth into the embankment shape. Every metre of height had a strip of grass planted, to hold the embankment together. - John Coast - Railway of Death

The daily routine of enforced labour would continue with only the occasional day off until the section of the line nearest the camp was completed. The fittest men were then moved onto other camps where conditions could sometimes change from bad to worse. The men at Chungkai worked on the construction of the railway line north towards Wun Lun camp about six miles away.

After months in captivity most of their uniform was in tatters or had long gone. They tried to patch up and repair what they could but many had resorted to wearing a loincloth made from the remnants of whatever clothing they had managed to salvage. Only a few were lucky enough to have some form of serviceable footware, most boots having long since fallen apart meant many men were now walking barerfoot.

When they had arrived from Changi many of the prisoners were already in poor health. A near starvation diet, lack of proper medicines and the extra physical demands of work on the railway in the heat and high humidity of the tropical jungle began to overwhelm the men.

Many had already succumbed to Malaria and had suffered recurrent bouts of Dysentery and Beriberi but the one thing they all feared was tropical ulcers.

Spikes of needle like bamboo shoots lay everywhere across the jungle floor. Without clothing for protection a prisoner who was unfortunate enough to receive a scratch or cut on the shins or ankle could soon be in serious trouble. The cuts rapidly became infected open wounds which turned into ulcers eating deep into the flesh. The Japanese refused to supply basic medication which could have been used to treat this devastating and life threatening condition and the situation became so bad that special Ulcer Wards were set up in the hospital huts.

In the Ulcer Wards, the stench of decaying and rotten flesh and bone made it practically impossible to walk through them. Amputations were being done every day, 24 legs were taken off in one day, either above or below the knee. The Surgeon used a knife for the flesh and a hacksaw for the bones. Treatment was very poor, dressings insufficient, only able to be dressed every two days. Wounds were scraped every two days without anaesthetic with a spoon, or blue bottles were allowed to settle on the wound, maggots were allowed to breed and to eat away the decaying flesh and then pulled out by tweezers. - Freeing the Demons - Alfred Edward Nellis

The most terrifying and hideous of all our diseases in those days, were the ghastly tropical ulcers. When resistance became reduced to a low ebb, the flesh would often commence to rot away. Sometimes the commencement could be attributed to a scratch, bite, or other wound, but often the ulcer would start spontaneously with a spot or blemish on the skin. Once started, they would sometimes enlarge at an amazing speed, and the foul stench of putrefying flesh kept away all but the Good Samaritans, and our ever-faithful medical orderlies. An active ulcer looked much like a lunar crater, and our only medicine was brine.

The screams coming from the ulcer hut each day told us that the orderlies were trying to squeeze out the pus that advanced between muscle and sinew, as, once in the bloodstream that caused rapid death. When the critical stage of the ulcer passed, it would sometimes start to heal faster than one would have believed possible, muscle, sinew and bone tissue being re-generated in an incredible way. Skin could not advance quickly enough from the edges of the wound, so at this stage Major Moon would perform the skin-graft operation. These were performed with home-made instruments such as needles stuck in corks, but a surprising number were successful.

If the ulcer would not pass the critical state, as a last resort to avoid amputation the wound would be scraped out with a sharpened table-spoon, the patient held down the while by three or four orderlies.

The Will to Live - Len Baines

Roy suffered a tropical ulcer on one leg just below the knee. He would sometimes talk about the unbearable pain. He said it was hard to describe conditions in the hospital huts and of the many men who were in a much worse state, who lost limbs as a result of this horrific disease. Fortunately his wounds eventualy responded to treatment but the mental scars remained.

For their labours the Japanese paid the men according to rank. Privates received ten cents a day whilst officers received between thirty and fifty dollars a month. Roy remembered being paid fifteen cents a day but said that the men always received much less after deductions were made for food and accommodation. Payments were often aggregated for a camp unit and the British commander would use some of the money to buy extra food and whatever medical supplies they could obtain for the hospital wards.

Most camps had a perimeter fence but security was not always strict. For anyone trying to escape, survival in the surrounding jungle would prove almost impossible. The Japanese also made it known to the local Thai population that they would be rewarded if they informed about any escaped prisoners. Some men did try to escape but almost all either perished in the jungle or were captured and executed.

What little money the men had would be used to barter with the Thais outside the camp gates or with traders in the barges which piled the river Kwai usually under close supervision by the guards. Tobacco was high on the list as were food items such as eggs, fruit and palm sugar. These items were essential to supplement the meagre food rations the troops received. A typical day started with a breakfast of boiled rice and tea (with demerara sugar if it was available), at mid-day it was boiled rice,tea and salt. An evening meal of boiled rice was supplemented with a watery stew (made from whatever vegetables were available) and tea. Meat was rarely made available.

In many of the camps the men had to endure appalling conditions and were it not for their skills and ingenuity in improving sanitation and living quarters to make life more bearable, many more would have perished. Getting a good nights sleep was almost impossible on the cramped conditions of the bamboo platforms because they were teeming with lice and bugs. To make matters worse, very few men had any sort of protection from the swarms of mosquitos which plagued them throughout the night.

The sanitation arrangements were no better and had to be constructed by digging deep pits which became the source of millions of flies which carried numerous infections.

As the Christmas of 1942 approached many of the men's thoughts turned to home and their loved ones who didn't’t know whether they were dead or alive. Since being captured in Singapore ten months ago most of the men had only had one or two opportunities to write home. This was done on one of the standard postcards which didn't allow any supplementary information to be added, all of which was passed by censors.

Work on the railway continued into 1943 and throughout the early part of the year more work parties were arriving by train from Changi. As they arrived at Ban Pong they learned like others before them that they were going to build the railway linking Bangkok with Burma.

In April that year the Japanese brought forward the scheduled completion date for the railway from December to August 1943. This push to advance the completion date became known as Speedo. What followed was one of the most notorious and brutal periods in the construction of the railway which lasted until it was finally completed in October 1943 at the cost of thousands of lives.

To achieve their objective the Japanese moved large numbers of troops from Changi to allow work on the middle and northern sections of the railway. The men who had laboured on the railway from the beginning were already undernourished and exhausted from their forced labour and many lay in the hospital huts, the victims of tropical diseases and malnutrition. This mattered little to the Japanese who had a total contempt for the sick (even their own) and if a man could stand he was considered fit for work on the railway. Those in the hospitals who were too ill to work were put on half rations, such was the inhuman treatment meted out by the Japanese.

Almost one half of POWs labouring on the middle and upper sections of the railway in northern Thailand died during the speedo period. This death rate compares to perhaps ten per cent or less in the base areas. What I saw in the Kanchanaburi Hospital Camp and in work camps later on was Japan’s total contempt for sickness. As indicated previously, sickness was equated with dishonour and shame and even with sabotage if it created problems in filling the day’s work quota. In their distorted view, the justification for sending sick and starving men to work in sometimes appalling conditions may have been to make unworthy men more worthy. The facts that it killed many of them and that human beings work better if they are reasonably well fed, have access to medicine and are not grossly overworked, never challenged this dogma. Ken Adams - Healing in Hell

Some of the heaviest casualties of the speedo period were from one of the last units to leave Changi in late April 1943. Known as F Force they consisted of 3600 Australian and 3400 British troops. After reaching Ban Pong, they were forced to march almost 300km to the most northern camps of the railway. Many died during the march north and eventually over 2000 British and over 1000 Australians from this force perished while working on the railway.