The Railway Ends, the Journey Continues

In October 1943 the northern and southern railway work parties came together and the line was finally joined at Konkuita (about 10 mile south of the Three Pagodas Pass). The completion was officially marked by the Japanese at a ceremonial opening.

The 258 miles of the Thai-Burma Railway (which became known as the Death Railway) had been built at a huge cost. Thousands of allied prisoners had perished and an enormous number had suffered ill health, brutality and misery at the hands of the Japanese during the many months of construction.

For some of the men who survived, their forced labour would continue on the railway for although the line had been completed further work was necessary in maintaining embankments and rebuilding weakened bridges to ensure it remained fully operational.

Those men not required for its maintenance were moved from 'up country' back to the base camps but by this time the nature of some of the larger camps such as Chungkai, Kanchanaburi and Nong Pladuk had changed completely. Due to the large numbers of sick and injured men who had been moved during the 'speedo' period more hospital huts were needed. By one estimate so many sick had arrived at Chungkai that the hospital started to take over the camp with only three out of the twenty huts remaining for fit prisoners. At its peak Chungkai held around two thousand patients.

After only a brief respite, many of the men who had been involved in the railway construction were sent sent by train back to Singapore. On arrival there some were put to work on the docks but thousands were loaded like cattle into the holds of steamships (later known as Hell ships) which would sail in convoy in the South China Sea. These men had once again to endure terrible cramped conditions (up to 1500 men per ship) with no sanitation as they were transported to their destinations in Japan and Taiwan where they would be put to work in the mines. Sadly many of the prisoners who had survived the Death Railway perished during this perilous journey. A number of the ships were torpedoed by American submarines who were unaware of their human cargo with very few being saved.

No. 1 PoW Camp - Nong Pladuk

Although it may have been earlier I believe it was around November/December 1943 when Roy was moved to his next camp - Nong Pladuk.

Nong Pladuk was almost 40 miles from Bangkok and one of the larger base and administration camps on the Thai-Burma railway. Situated at the junction of the lines from Singapore and Bangkok it was initially built to house up to 2000 prisoners but later that capacity increased almost four fold. to around 8000. The camp was split into two units known as No.1 and No.2 camps. The No.1 camp contained British, Australian and American prisoners while prisoners from the Netherlands were billeted in No.2 camp. Both camps were about a mile away from the railway junction where there were supply depots, marshalling yards and the railway engineering and maintenance workshops known by the names of Hashimoto's, Sachimoto's and Kanimoto's.

For the next fifteen months Roy was based in the No.1 camp although he recalled that on several occasions he travelled with small work parties who were required to move back 'up country' for short periods to carry out maintenance work on the railway line. The work at Nong Pladuk was still demanding for the men who for many months had been kept on a near starvation diet consisting of mainly rice and the occasional watery stew. Most days Roy and his comrades made the one mile journey from camp to the railway sidings and marshalling yards where they were set to work loading and unloading materials, rails and sleepers. For a time Roy worked in Hashimotos workshops where he was involved in the repair of diesel rail units and Japanese military vehicles.

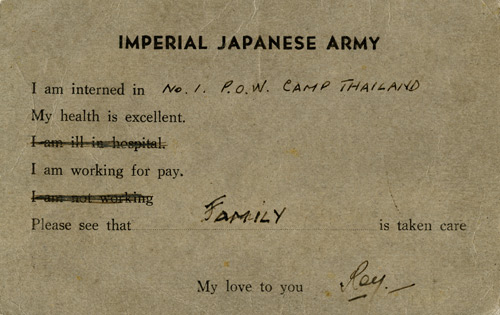

Back home Roy's mother was still anxiously waiting news of his whereabouts. Like many of the PoW's loved ones she wrote numerous letters hoping that she would eventually receive a reply.

The only mail Roy's mother received in almost four years.

In almost four years of captivity Roy's mother received just the one postcard (above). It was written by Roy when he was at Nong Pladuk. Some were lucky enough to receive mail from home but deliveries were few and far between and many of the men (Roy included) received no mail during the whole of their captivity.

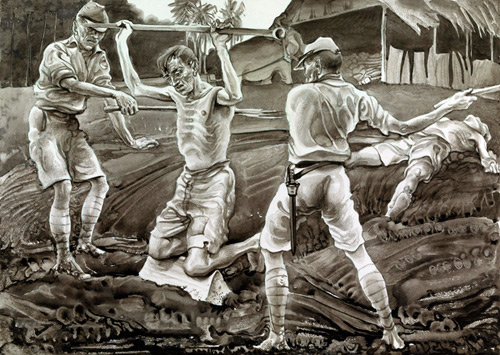

The pace of work was not as relentless as it had been when the railway was being constructed and the number of rest days became more frequent but the men were still treated badly by their captors and the guards often resorted to violence. The camp guards were mainly Koreans many of whom abused their authority. Prisoners were made to bow in the presence of any of their captors, Japanese or Korean. Failure to do so resulted in face slapping often followed by a kicking or beating if the prisoner flinched. The men had learned that they had to endure such humiliation for if they tried to resist, more serious punishment would follow.

I don't know if Roy was ever on the receiving end of such beatings but if he was he never talked about it. However, he did talk about some of the punishments handed out to other prisoners. On more than one occasion he had witnessed men being made to stand for hours in the baking sun while holding heavy rocks in their outstretched arms. When they could no longer endure this torture they were beaten with bamboo canes. Another horrific incident he recalled was where a prisoner was held down while guards forced water down him until his stomach was swollen. The guards then took turns to stamp on the mans abdomen until he passed out. Roy didn't know whether the man survived but didn't see him again.

Roy never had a good word to say about any of the guards but held the Thai people in high regard. He talked about how they helped prisoners by smuggling food and sometimes medical supplies into the camps and how they often passed fruit to the men on their long marches between camps, risking a severe beating from the guards if they were caught. Over the course of the the conflict the help given by the Thais helped save many lives.

It was in August 1944 when Roy was hospitalised for a short time with his first attack of Malaria. He was fortunate not to have succumbed to this debilitating disease before then as many of his comrades had not been so lucky. It occurs in several forms, some fatal. After a short time he recovered but would suffer with recurring bouts for some time after.

In the latter part of 1944 the prisoners faced a new threat, this time from Allied air raids. The close proximity of Nong Pladuk camps to the strategic targets of the Japanese storage depots and workshops meant that bombing raids were inevitable. All along the Thai- Burma railway key bridges and depots would become targets.

One such raid occurred around September 1944:

When the bombers kept flying over it lifted our spirits because we thought the war would soon be at an end. One night they came over very low and we heard the bombs whistling as they fell to the ground. We didn't know whether the bombers knew we were prisoners in the camps but we thought they must have known by now. The explosions went on for a long time and we could see fires all around. They started to come nearer and the only place we could shelter was under the huts. Some of the bombs dropped in our camp and lots of men were injured by flying shrapnel and a lot were killed.

After the fires died down the camp was in darkness and it was not until some hours after the raid that the full extent of the destruction and loss of life became apparent. Around a hundred men had been killed and many more had sustained horrific injuries. The next day all the bodies were recovered and buried in a mass grave. It was a sad end for the men who had suffered for many months only to be killed by their own bombs. This incident caused a great deal of resentment among the men who could not believe that the Allied Command were unaware that a PoW camp was located next to their targets. Sadly the bombing raids continued for several months and the death toll from them increased.

Throughout 1944 the camp commander was Lt. Colonel Toosey who arrived in Nong Pladuk from Tamarkan in December 1943. After the air raid Toosey made strong representations to the camp commander to allow the digging of slit trenches which would afford the prisoners at least some protection from the air raids. Toosey had gained enormous respect from the men under him for the way he handled the Japanese and also for how he always tried to secure the best conditions for the prisoners.

He did his best to improve morale amongst the men by securing concessions to allow entertainment whenever possible and in a move encourage camaraderie he made officers and men eat together, something officers in the regular army were very much against.